by Diana Foxall

When what is now BCEHS began back in 1974, Ray Sims wasn’t tall enough to be hired as a paramedic. At 5’4” and 145lbs, he fell short – literally – of the hiring standards of the day, which required would-be paramedics to stand between 5’8” and 6’2” and weigh at least 150lbs.

But Ray, who celebrated his 50-year anniversary with BCEHS this past October, had a creative solution ready for his interview.

“In 1974, the social scene is discos, and [for] discos at that time, [you] wore 2” or 3” platform shoes,” he recalls. “Did I have a pair of platform shoes I could wear? Yes, I did.”

“So, I had to wear my platform shoes, which raised me up to almost 5’7”. I was a little short, but I was okay, I was taken in – and they waived the underweight bit.”

Ray continued to wear his platform shoes on the job to keep up appearances until he eventually twisted his ankle, telling his supervisor he would have to accept him as he was, height and all.

However, his stature would prove challenging in other ways. Ray had grown up in Vancouver, and after graduating from the Emergency Medical Assistant (EMA) II – now known as primary care paramedic (PCP) – course, his supervisors recognized the value of his local knowledge and wanted him behind the wheel when he was partnered with colleagues who weren’t from the area.

“This is back in the day of the hearse-type limousine Cadillac ambulances. They had a bench seat in the front and all the paraphernalia for splinting was in behind that seat,” Ray said. “My platform shoes didn’t help with driving; when I got in behind the wheel, I couldn’t see over the steering wheel – I looked through it – and if I moved the seat forward enough to touch the pedals, all this paraphernalia jammed the seat, which meant you had to stop, pull everything out, put the seat back, and repack it for anyone else to drive the vehicle.”

Ray’s driving trainer tried to problem-solve by adding blocks to help him reach the pedals, which was unsuccessful. Eventually, the trainer created a customized pillow contraption that allowed Ray to see over the steering wheel, which he had to bring along with him everywhere he went.

In 1975, the first EMA III paramedics, now known as advanced care paramedics (ACPs), began hitting the streets. This new license level attracted significant interest from paramedics who wanted to learn to use new tools such as intubation, IVs, airway support, and resuscitation skills. Demand for spots in the EMA III program, which required three years plus a day of experience, was high and space was limited.

As Ray looked for a fresh opportunity to keep expanding his skill set, he decided to apply to the newly created Infant Transport Team (ITT) program.

The team is a highly specialized group of paramedics who care for neonatal, pediatric, and obstetric patients – though when the program began in 1976, their work was limited to tiny newborn babies. ITT was originally known as the “High Risk Infant Transport Team” when it first began, but the “High Risk” was soon dropped from the name so as not to alarm the parents of the patients.

Initially, ITT paramedics were largely meant to support the physicians who attended calls involving neonatal babies and to look after the equipment the doctors carried with them. The training involved a collaboration between Art Berry, a registered nurse who ran the service’s learning department, and Dr. Margaret Pendray, who was head of the nursery at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH).

“At the time, we would go down to VGH and we would pick up a physician and an incubator, drive them out to wherever, and the physician would go in by themselves with the equipment, we’d go for coffee,” Ray said. “Then we’d come back and they’d be all, ‘Hurry!’ because as soon as they walked in [to the hospital], the staff disappeared because this was a new thing: the field that we were working in is called neonatology.”

The neonatal period is a baby’s first four weeks of life, and as a medical specialty, it didn’t really take shape until the mid-1960s. Much of the early work and research in neonatology was done in Denver, Colorado, and by the time ITT came into being, the field was still very new and somewhat mystifying even to those in medicine.

“When I started, 32 weeks was the cut off,” Ray said. “Anything younger than that, they were deemed non-viable. When I was in training, I can remember a 25-weeker being born in the [emergency department] at VGH on my first shift.”

“I was just tasked to sit there and wait for that child to expire. That’s quite a thing. I was 22 years old and sitting there and watching; stopped breathing, go blue, get cold, and the heart was still beating away – not enough to maintain life, but you realize how strong these children are.”

In 1977, Dr. Andrew Macnab, a British physician, had arrived in Vancouver and was conducting research at VGH’s nursery. The ITT paramedics began training with Dr. Macnab, which included learning the medical model – a departure from the protocol medicine model that was used by the ambulance service at the time. The education ITT paramedics received began increasing, with Thursdays becoming a training day for the team.

For nearly the first two decades of ITT’s existence, its paramedics worked out of station 243 on the west side of Vancouver, responding to all kinds of events, not just ITT calls – meaning they were taken off their regular shifts to transport babies on an as-needed basis.

“We were on an ambulance and we were doing ambulance duties, and if the [ITT] call came in, we would finish and be dispatched to do that call,” Ray said. “That was a very quiet area for call volumes so [paramedics could] afford to be pulled from that area.”

When Dr. Macnab moved from the nursery at VGH into the ICU several years later, ITT paramedics branched out into the pediatric world. At that time, pediatric patients arrived at the hospital with general duty nurses and often hadn’t received adequate pre-hospital care. In 1981, the team’s base shifted from VGH to Vancouver Children’s Hospital (VCH) in Shaughnessy.

“We’re now doing kids up to 17-years-old – we’re doing the traumas and other issues, not just babies. We’re still the Infant Transport Team, but I’m transporting a 14-year-old,” Ray said.

The addition of pediatric patients to the team’s repertoire kept the team busy, and towards the end of the 1980s, ITT’s scope expanded further to include maternal care. The team’s existing expertise with neonatal care and transportation meant they were well-positioned to handle the unique challenges of transporting high-risk maternity patients. For the first time, the ITT started working with adult patients.

The three distinct specialties offer a unique experience for paramedics.

“I can start off my shift and do a 25-weeker – a child that will fit in my hand, weighing under 2lbs. My next call can be a 14-year-old newly diabetic who is extremely sick, and top that off with a woman in preterm labour,” Ray said.

By 1995, the call volume for ITT was competing with the team’s volume on the street. Both the street work call volume and the interfacility ITT call volume were increasing rapidly, and the tragic medevac plane crash in Haida Gwaii in January of that year that killed two ITT members created a sense of urgency for change. By April 1995, the team was pulled off the street work so they could respond exclusively to ITT calls, moving into what was intended to be a temporary station at Children’s Hospital where they remain today.

Reflecting on his 50 years as a paramedic, Ray says it’s a different world altogether from the beginning to where we are now.

“I came in with a first aid ticket to do this job, and at my level, I would be a master’s degree at what I’m doing right now,” he said. “Treating all these different patients, the level of care and what we as paramedics provide for our patients, it’s mindboggling.”

“We do the same things: we attend to patients in crisis, we try to make things better for them, and we transport them to higher medical care. But in 1976, we were putting hot water bottles in the bed to keep them nice and warm at night. The closest thing to us [now] is a physician’s assistant.”

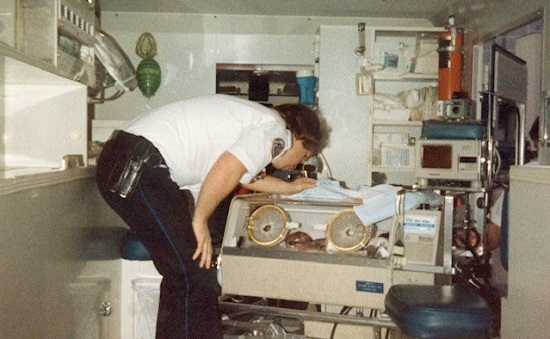

The difference in equipment that ITT uses now is similarly staggering. In the 1970s, Ray recalls using a single Plano 747 fishing tackle box to carry his equipment. There was an incubator and two tape-on monitors, that was it – no oxygen analysers nor SAT monitors, just a tiny needle that displayed a heart rate and a little temperature monitor. Now, Ray takes 16 cases on an Air Evac, which contain ventilators, securing devices, IV pumps, various machines for respiratory issues, and more.

Over the course of his career, Ray has worked with three paramedics whom he transported as babies. He said the experience is a tangible reminder of the value of his work, and notes that the ITT program has been so rewarding that he returned to work to support it after initially retiring in 2009.

“Children are our future. It took me a while to understand that, I was 22 years old getting into this,” he said. “When I do any type of training [for other paramedics], I say to them … ‘These patients come with a 75-year warranty, they just need a little boost and a little help, and once they get over the hump, they take off.”