by Nic Hume

Morris Lewinston Ebanks was born on March 31st, 1942, in the town of West Bay in the Cayman Islands. With only 6,500 residents at the time, the little Caribbean nation was blessedly sheltered from the worst of World War 2, and served as a relatively safe place for the young Ebanks to grow up.

As a teenager, Ebanks found work as a “messman” - someone who served officers meals and performed sundry tasks - on local cargo ships plying the local waters. While the position may not have been the most glamorous, it gave Ebanks a chance to see the world outside of the Cayman Islands. In a recent interview, Ebanks’ close friend, Terry Raappana recalled

“[Morris] grew up the Cayman Islands. Very Poor. Then he got a job on a freighter to get away from the Cayman Islands, then he sailed all around the world. And he thought maybe he was poor in the Caymans, but he saw abject poverty in other countries that blew his mind.

Going through the Panama Canal - The canal at that time was so narrow that the boat would be a couple of feet from the edge of the shore. One of his jobs would be to take a broom handle and to push people off, who tried to jump onto the boat.”

By the mid-60s, Ebanks was the lead singer of a Caymanian band called “The Marsihans”. Playing gigs at tourist bars on Grand Cayman, he met a young Canadian tourist named Audrey Monkman. Several years senior to him, Audrey later recalled Ebanks as being “quite arrogant and full of himself” when they first met.

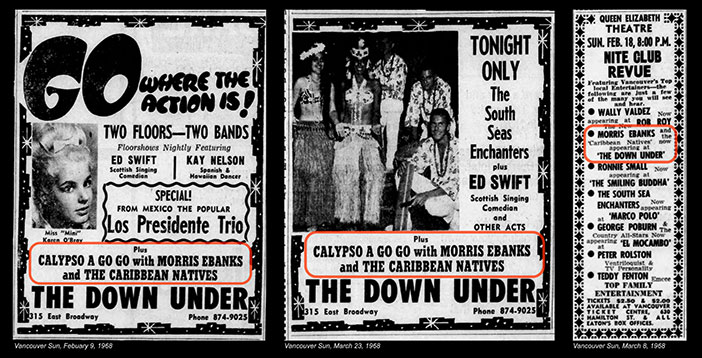

“Morris Ebanks and The Caribbean Natives” were a regular fixture at The Down Under, at 315 East Broadway. The building the housed the venue still stands. Ebanks - along with other notable Vancouver performers - also played the Queen Elizabeth Theatre as part of a “Nite Club Revue” night in 1968.

“Morris Ebanks and The Caribbean Natives” were a regular fixture at The Down Under, at 315 East Broadway. The building the housed the venue still stands. Ebanks - along with other notable Vancouver performers - also played the Queen Elizabeth Theatre as part of a “Nite Club Revue” night in 1968.

The band later went on tour, with Ebanks bringing his wife and two young sons on the road for a period of time.

A few months later, Ebanks traveled to Vancouver to see Audrey. They were married on August 22, 1967.

Morris wasted no time in securing work as a singer in his new Canadian home, and by the beginning of 1968, Morris Ebanks and the Caribbean Natives had a place as the backing band for Calypso a Go Go, a nightly feature at the Down Under Club at 315 East Broadway in Vancouver. The band - and Morris’s singing - were such a hit that the group even played the Queen Elizabeth Theatre as part of a night club revue, sharing the stage with TV ventriloquist Peter Ralston. Tickets were two dollars.

Success meant travel. Morris Ebanks and the Caribbean Natives went on the road, spending months based out of Kamloops. Audrey quit her job as a bookkeeper and, along with their two adopted sons Randy and Otis, went on the road with the band. 1972 saw the family return to the Vancouver area and adopt their third child; their daughter Mora.

Raappana recalls that during the ‘60s, Ebanks had assumed a large debt to pay for a parent’s medical care. The debt, along with his obligations to his growing family seem likely to have pushed Ebanks towards employment that is more stable than night club singing gigs and the life of touring musician.

How exactly Morris was lured into the ambulance service is a story that has been lost to time, but by the late 1960s or early 1970s, Ebanks was working for Metropolitan Ambulance in Vancouver. Morris was at first a casual worker, still singing in the evenings, and later a full-timer on a 24-hour car. When the private operator was merged into the Provincial Ambulance Service in 1974, Ebanks was one of the first to make the switch.

Terry Raappana remembers as a young man in 1975, hanging out at a restaurant called The Starlight, at 16th and Oak in Vancouver:

“A lot of the paramedics would come in for coffee. It was run by a Greek family, and the place was really a hangout. That was many things, but from my point of view the paramedics would come down and talk to each other, and to all the young people - like me - who were there. And they would tell these ambulance stories… They’d sit there and have a huge amount of young people who would listen to them, and out of those young people, quite a few became paramedics.

Morris was there.”

It’s impossible to put a number on how many paramedics were recruited at The Starlight, but Raappana wasn’t the only one.

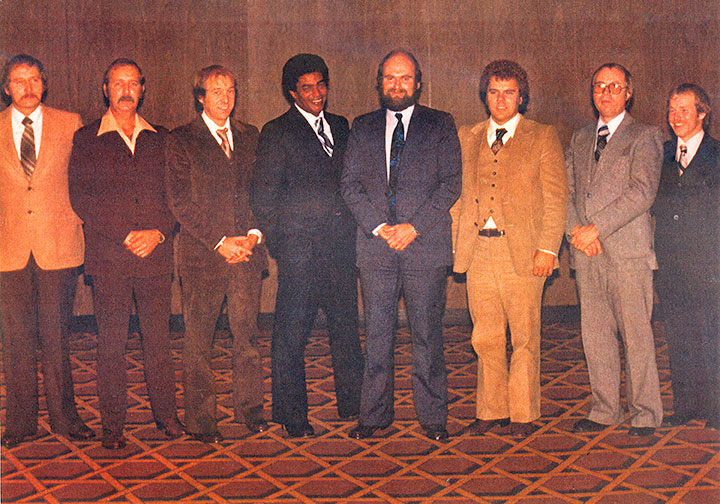

Morris Ebanks and Terry Raappana were close friends. This undated photo, from the early 1980s, shows the pair in the ambulance bay of St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

As the ambulance service grew throughout the province, Ebanks’ put his clinical and interpersonal skills to good use. Along with other BCAS pioneers in the ‘70s and ‘80s, Ebanks had a reputation for a genius-level intellect and a remarkable warmth and kindness that made him an exceptional teacher. “[Morris] would talk to you, and within a minute, he’d be teaching you something.”

At the same time, as the provincial service evolved, Ebanks had a decision to make:

“He had a tremendous voice. He could sing. He was on the edge of making it, he told me… But he had [a stable] job with the Ambulance Service, and he had to make a decision. Does he stay in entertainment, or does he go with the Ambulance Service? “

Ebanks’ choice was clear and the rest was history:

“He stayed in the ambulance service, and fairly rapidly [qualified as an EMA II, and beyond] … and he [ended up talking to] Dr. Pendray at Children’s Hospital, and they said ‘hey, you’ve got all these sick babies around the province, and we’ve got paramedics who are capable of taking care of them. If you were involved in organizing a training course, maybe we could do some good for the mothers and the children, and it would also be good for the paramedics who want to learn, and grow.’ … That’s how the ITT was born.”

Raappana is quick to note that while Ebanks was pivotal in forming what is now the ITT, there were many others involved as well. “I believe he was with Vince Shea [during those initial conversations… There’s always other people involved. It’s impossible to do it all yourself… Except maybe for Morris…”

It was only a few years later that the province of British Columbia graduated the first class of paramedics qualified to work as the “High Risk Infant Team”. This team later became the Infant Transport Team, and cares for neonates, infants and high-risk maternity patients across B.C.

Ebanks spent much of the rest of his career working around BC, caring for many of the most vulnerable and sick babies in the province. And what’s more, he did it in style.

“[He] was so phenomenal and helpful to many people. I still run into people in the service [who remember him.] Flying around the province, he was that jovial, friendly, singing paramedic. He had that way with people. He’d go up-country to pick up a baby from some 6-month paramedic, and they’d be scared to hell [with a sick patient] and Morris just had a way of disarming them and helping them relax and be good at their job. And to this day, you’ll run into people, and they’ll have a story with him. They’ll say ‘oh, I did a call with him at the Yukon border, or I did a call with him in some town I’ve never heard of…”

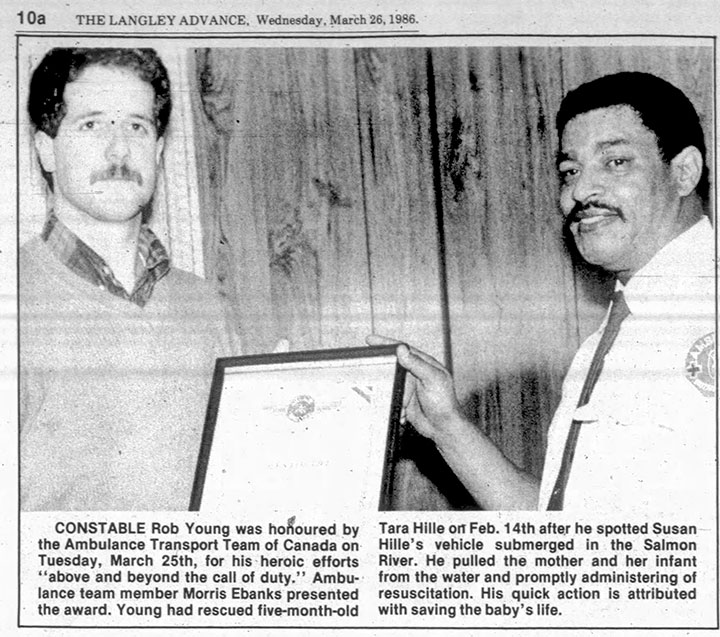

Morris was known for his leadership, and support of those around him - Including presenting awards and recognition on behalf of the ambulance service.

Ebanks’ contributions weren’t limited to his clinical skills, nd he spent much of his career deeply involved with union work with the APBC, both as a union trustee, and also as a mentor to others. “He was able to do good union work. He was able to see winds of change within the union, within the service, and an appropriate way to go… He took people under his wing [and supported them.]”

Ebanks quickly earned himself a reputation as someone who could “put out fires… And he was good at it, because he put out big fires… He was a warm-hearted individual with a big heart, and he just got people to like him fairly quickly.” His skills at resolving conflicts became the stuff of legend, and Ebanks often found himself traveling around the province not just with ITT, but to support conflict resolution and mediation efforts.

By the late 1990s, failing health had forced Morris into an early retirement. He remained well-loved by many, with Raappana visiting him regularly.

On March 14, 2001, just before 4 p.m. Morris Ebanks died at Peace Arch Hospital.

Morris’s final resting place is nestled beside the beach in West Bay, on Grand Cayman, in a small, densely packed cemetery. A white picket fence separates the multitude of graves from the soft, white sands of Seven Mile Beach, and the warm Caribbean Sea.

Morris Ebanks legacy of supporting young paramedics is carried on today with the Morris Ebanks Memorial Scholarship, administered by the APBC.