by Diana Foxall

In fact, he’s been serving the province since even before the provincial ambulance service was formed in 1974, with his first medical call coming during the final days of December 1973. There are two other BCEHS paramedics who are also marking 50 years of service this year – Ray Sims and Martin Hennigar – but Peter was hired first.

“As a first responder, [being a medic] was part and parcel of being hired in a remote area working for a government agency,” Peter said. “I started with BC Parks service in Manning Park in 1973, and because of the isolation – we were 41 miles from any township – we had a Ford Econoline van, we had a fire truck, and we had a group of individuals that made up what they called the Manning Park Emergency Services.”

Peter and his colleagues wore many hats at that point in time, acting as paramedics, search and rescue, fire suppression, park rangers, and conservation officers. Unsurprisingly, the communication technology in that day and age was also quite different from the current day – especially somewhere remote like Manning Park.

“There were no pagers, you were lucky if you could find a radio, and there were definitely no phones – so we had airhorns,” Peter said. “If there was an emergency, the airhorn would go off within the operational area of the park, which was headquarters, and everybody would assemble at the fire hall where the ambulance, the fire truck, and the first aid room and rescue gear were located.”

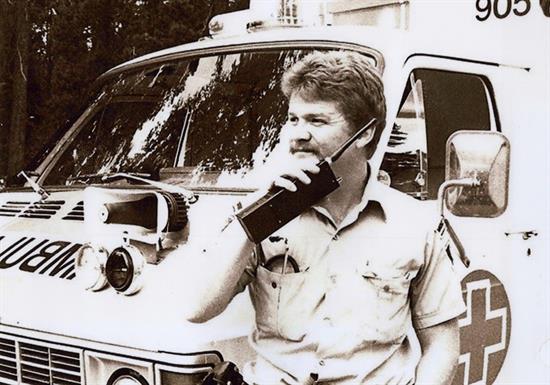

Pictured: Peter Marochi in Manning Park in the 1970s.

As the BC Ambulance Service prepared to begin operations in 1974, Peter said that the medical training at Manning Park became more structured. All staff who worked on the ambulance in the park went through the Emergency Medical Assistant (EMA) I workshop and had to obtain their industrial WorkSafe ticket and Class 4 driver’s license. But because Peter was so young, he couldn’t drive the ambulance until after April 13, 1974, when he turned 19.

“When we did an ambulance call, we prioritized whether or not we were going to use the truck with a stretcher,” Peter said. “We would put people in vehicles – we would put people in patrol trucks, BC Parks Ranger patrol trucks – and we would take them to Hope or Princeton that way. That ambulance had one stretcher and it was solely designed for high acuity.”

“It was part of our ongoing training in that first infancy stage, how to load four people into that Econoline van – two from the ceiling, one on the main cot, and one on the side bench. Four people!”

Several years passed, and in 1979, Harvey Bull and Jim Fissel – two BC Ambulance Service pioneers – were able to bring a regular ambulance to Manning Park. Because of the park’s topography, Peter said the ambulance wasn’t just any old ambulance: it had special gearing in the rear end and a certain engine that gave it enough juice it to traverse the park and get up and down the mountain pass.

Pictured: Marochi in Manning Park.

Pictured: Marochi in Manning Park.

In 1983, Peter’s time at Manning Park was up as the resort privatized, and he was given a choice between five options for his next destination: Haida Gwaii, Fort St. John, Fort Nelson, the Sunshine Coast, or Squamish.

Devastated by the resort’s shift to privatization and ultimately the loss of his position in the region that he loved, Peter got his first taste of the mantra he stands by to this day, “everything happens for a reason,” and so began the first evolution of his non-linear career.

Peter decided on Squamish based on advice from his zone manager from Manning Park – but actually getting the job wasn’t exactly a breeze. He got in touch with the Squamish unit chief and dropped off a resume, but struggled to secure a position as part-timers often scooped up extra hours doing call-outs and transfers. He was encouraged to be patient and bide his time, and eventually that patience paid off.

“I’m living about half a mile from the ambulance/fire hall/police station in Squamish in 1983, and there was an MVI at Britannia Beach,” Peter recalled. “[The unit chief] grabbed a spare fire truck/rescue van, equipped with two Furley [stretchers] on the floor, and he said, ‘Would you go with me? We have no resources.’ So I went.”

The response ended up being particularly challenging, involving several critically injured people, and upon returning to the station for a post-response debrief, Peter received the nod he’d been waiting for as the unit chief addressed the station: “Peter is now an operator at 222 in Squamish.”

But Peter’s official transition from BC Parks to BC Ambulance Service in Squamish almost didn’t happen because he had been unable to attend the requested in-person interview, as he was in Ottawa to receive the Medal of Bravery for his role in a river rescue where he helped save a couple whose vehicle had plummeted into the Similkameen River in 1982.

“The day I did the river rescue for 4.5 hours and almost drowned, I was just coming off my last night of two weeks of night shift coverage [in Manning Park],” he said. “At 7:07 in the morning, I’m putting everything in the patrol truck to take over to headquarters and I hear Manning 3 calling for Manning 10, which was our call letters, ‘Has anyone got a boat?’ So I responded as Manning 8, which was my call sign, and I said, ‘What’s up?’ And they said, ‘The other Pete’s in trouble down the river, there’s a vehicle – a pickup truck – in the Similkameen and it’s freshet.’”

His interview was ultimately conducted while he was in Ottawa receiving recognition for his efforts in the rescue.

“I got hired over the phone and [the personnel officer] told me when my start date was. He said, ‘When you get back here, you’ve got to fill out some paperwork’ – and I got the distinct sense he didn’t quite believe where I was.”

“Everything happens for a reason.”

After spending some time at the Squamish station, Peter transferred to the Downtown Eastside – and almost decided his time in paramedicine was done. Despite years of training and experience, nothing had prepared him for working on the Downtown Eastside, and he considered quitting multiple times over the two years he spent as an EMA II HRSB at Station 248. The challenging care and complex populations, further complicated by grueling scheduling patterns, left him at a crossroads.

“They would schedule you [at times] for 24-hour shifts. I would work the southeast slope for 10 [hours], and then pull a 14-hour night shift in town,” Peter said. “So I get home, and I’m thinking ‘I can’t do this, I physically can’t do this.’”

At that time, he began considering pursuing a conservation officer job on the Sunshine Coast, where a position had opened up, but ultimately stuck with paramedicine.

Seven years later, when his station manager informed him and the other senior staff that they were considering transitioning their shifts from high acuity to a transfer car rotation, he had a decision to make: leave the city, or pursue advanced life support (ALS) training. With the encouragement of his colleagues and mentors, he doubled down on his commitment to the field and enrolled in the ALS course.

Peter describes the first part of the program as “a huge wakeup call.”

“Three months into the course, I was sat down by senior medical oversight and I was given the opportunity to go back to my station and pursue something else,” Peter said. “I had the street knowledge, but medicine at that level did not come easily initially.”

He recalls this conversation as a turning point, and told his supervisors he wasn’t quitting. They explained what he needed to do, and he rose through the ranks of his ALS class.

Pictured: Peter Marochi's ALS class. Marochi is in the second row, second-from-left.

Pictured: Peter Marochi's ALS class. Marochi is in the second row, second-from-left.

Peter went on to spend 18 years as a full-time ALS paramedic, now known as an advanced care paramedic (ACP). Eventually, his higher acuity work led him to the ambulance station at Vancouver International Airport, where he “entertained” taking the AirEvac course – but a chance conversation brought him back to his roots in the Fraser Valley.

He was at his father’s house in Harrison Hot Springs when two senior ALS members who had moved from Vancouver to Agassiz and Chilliwack respectively popped in for a beer. They suggested Peter apply to Chilliwack, which he immediately nixed, but they encouraged him to consider it, saying the Chilliwack station did good volume – and it was one of the few places that had ALS at the time.

After some time to think, Peter decided to make the jump, and eventually encouraged one of his mentors from Vancouver to transfer to Chilliwack as well. The two partnered up for more than 16 years, retiring from full-time service together in 2010.

Shifting away from permanent full-time work post-‘retirement’ wasn’t the smoothest transition for Peter, and he considered walking away during the first few years because of the scheduling challenges. But as Peter says, everything happens for a reason, and the unit chief in Abbotsford – who Peter trained in the 1980s – asked if Peter would consider temping to the Abbotsford station, where he continues to work part-time today, in addition to teaching and working for EMALB, the provincial paramedic licensing board.

As he looks back, Peter reflects that he’s had his fair share of full circle moments in his half a century paramedic career – but one of them stands above the rest.

“My journey all started with my Papa – he said, ‘I’ve got you a job at Manning Park!’ I said, ‘What? I don’t want to go to Manning Park!’” he said. “‘I got you a job, you’re going to Manning Park.’”

“I put five days in and I came home. I’m 18-years-old driving the Hope Princeton Highway in a 1968 Cortina. I get home and I say ‘I can’t go back, I can’t do it.’”

“He said, ‘Go back, stay up there on your days off, don’t come home.’”

“We worked five [days on] and two [days off] – I think I had Tuesday and Wednesday off. So I stayed there, and all of a sudden, you meet new people: you’re 18-years-old, next thing you know I’m not home for a month. Next thing I know, I’m mailing my cheques home – I wasn’t going home for a couple months.”

Peter’s most difficult moment as a paramedic came more than 50 years later in May of this year – and also involved his father.

He was at the Agassiz-Harrison Rod & Gun Club on standby while law enforcement staff did their long gun training when he received a call saying his 91-year-old father had had a cardiac event while out in the garden tending to his tomatoes. He jumped in the car and quickly got on the phone with a paramedic specialist and dispatch.

“I’m enroute in my personal vehicle to get there so they don’t do a resuscitation against my father’s wishes, because the house is locked and the code status is on the fridge inside,” he said. “Fire services volunteers and primary care paramedics [PCPs] were getting him out of the garden and starting CPR.”

Peter stopped the resuscitation efforts over the phone, in keeping with his father’s explicit wishes, and allowed the man to whom he attributes his career, successes, and character to pass on in the peaceful garden of his childhood home.

“The most difficult call of my career.”

And while the saying goes “lightning never strikes twice,” Peter has been around long enough that he’s experienced a few unlikely coincidences.

He recounts a call he did at Manning Park with a helicopter pilot when he was with the parks service: “…a young lady got kicked off a horse and she was severely traumatized – and here I’m just a basic first aider,” he recalls. “I did [an identical call on] a different young person as advanced life support 25 years later with the son of the first pilot.”

The father and son pilot duo reportedly still talk about it to this day.

Peter’s enthusiasm for paramedicine is contagious, and he says the improvements that have been made in communications, technology, equipment, and support over the years are “unbelievable, literally unbelievable.”

“Giving us LP-15 monitors in the PCP community has changed outcomes of patients. I’m not saying it’s on every truck in the province, it’s not – it’s only in certain designated areas,” he said. “But if used appropriately in accordance with the treatment guidelines, they change lives.”

He recalls a particular case where an Agassiz crew utilized an LP-15 monitor/defibrillator on a 76-year-old patient, allowing the crew to recognize the need for an advanced care intercept early on and ultimately support the timely provision of life-saving interventions. After the patient was transferred to Peter’s team, they were able to successfully make the 40-minute journey to Royal Columbian Hospital. The patient in question was in fact one of the original physicians responsible for implementing ALS services in Chilliwack.

“He benefited from the care of [advanced cardiovascular life support] in the small town that he helped originate it back in the early 80s,” Peter said. “He was one of the original physicians, how cool is that?”

Pictured: Marochi in 1991, supporting the Infant Transport Team with the transfer of his baby daughter.

And it’s not just the gear that is night and day from 1974: Peter says the implementation of paramedic specialists as a clinical resource offers huge value to paramedics on-car, and education as a whole – including BCEHS’ Learning department, the paramedic practice educators, and the scope of practice expansion currently underway – is making a significant difference in the service.

As well, he says call-takers and dispatchers don’t get enough credit, extending his kudos to those doing this vital work.

“I’m on scene, I’m looking at what I need to fix or not fix,” Peter said. “They’re trying to navigate medical crises on a telephone – supporting people in distress, sometimes with non-English speaking individuals or people who have special needs.”

As he recently received his 50-year long service award, it’s worth mentioning Peter’s growing collection of accolades: he has received the Medal of Bravery, the Most Venerable Order of St. John of Jerusalem Life Saving Medal, and the RCMP Commissioner’s Commendation for Bravery – all for his role in the river rescue in 1982. He was also awarded the Emergency Medical Services Exemplary Service Medal, which is seen as the pinnacle of paramedic recognition, and will soon receive the King Charles III Coronation Medal. And despite all of this, Peter says he’s just a regular guy still doing his job – 50 years on.

“If you’re energetic and you like what you do and you bring it, things work out for a reason.”